LA NORTE

The first ascent of the longest, most direct line on the imposing north face of Cerro Torre, and its cost.

By Rolando Garibotti, 25/03/2022. [corrected 12/04/2022]

- Versión en español

[This article is copyrighted. Please do not reprint this article in whole or part, in any form, without obtaining written permission.]

In late January, and after years of attempts, Tomás “Tomy” Aguiló and Corrado “Korra” Pesce climbed a new route on the north face of Cerro Torre.

In 2013, with Nicolas Benedetti, Tomy attempted the north face for the first time. They did not have a clear strategy nor much information. They reached the base of the face via the American Torre Egger route, and managed to open six new pitches, reaching the "Burke-Proctor attempt” traverse, which exits the “east dihedral” onto the north face. In a section of wall thought to be blank and improbable, they found an obvious line, albeit a difficult, committing one. They retreated due to high temperatures and unpromising weather ahead.

In 2014, they tried again. This time Jorge Ackermann joined them. Conditions were challenging, with a lot of rime, which combined with high temperatures, and wind, forced them to retreat at the height of the English box, at the base of the “east dihedral.”

In the beginning of 2019, they were back at it again. Nico could not join them, so Korra took his place. With better conditions, and a strong team, they climbed a harder line in the lower quarter, starting via a variation called “Un Sogno Interrotto”, to then link into the American Torre Egger route. Once on the north face they repeated the six pitches Tomy and Nico had opened in 2013, and climbed three new pitches beyond their previous highpoint, reaching an obvious shoulder on the left edge of the face, “el honguito” (the small mushroom). In the second to last pitch, Korra took a fall, breaking his finger. Jorge finished that pitch - the “dedo machucado” pitch, but in spite of his broken finger Korra led the following one, an ice-goulotte - the “Hard Korra” pitch. They bivouacked at the “honguito”, but in the early morning when the wind increased, and with Korra’s finger begging for treatment, they retreated.

In early 2020, Jorge, Korra, and Tomy, joined forces again, but bad conditions did not allow them to get even close to the peak.

With Jorge busy with life in the northern hemisphere, Korra and Tomy met in Chalten in mid-January. Within days, a good weather window materialized in the forecast. They approached the Noruegos camp on the 24th, and on the 25th, finding the lower wall snowier than expected, they fixed the first three pitches, and went back to Noruegos. On the 26th they woke up at 1:15 am, approached, jumared those first pitches, and continued climbing. Around noon they reached a bivy ledge, at the height and to the right of the English box, 600 meters from the ground. This ledge is below the steep right wall of the “east dihedral”, a location that many thought was well protected from falling debris. They left much of their gear, and continued another 60 meters, to fix the first pitch on the north face itself, the route’s crux, that has a potential ledge fall - the “cuchillo entre los dientes” pitch (knife between the teeth). They then backtracked to the bivy ledge.

On the 27th, and to minimize the risk involved in climbing on the north face, which is crowned by rime mushrooms, they woke up at midnight, and started moving at 1 a.m, hoping to profit from the relative safety of the coldest hours of the day. They left behind their bivy gear, planning to climb to the summit non-stop. Tomy led away in the night, navigating difficult to protect, runout climbing on the steep north face. He had led that section twice before, but darkness and verglas made the climbing particularly challenging. In spite of this he made fast, steady progress, and soon after sunrise, and after seven pitches, at the base of an ice-goulotte, he passed the lead over to Korra.

One pitch lower, Davide Bacci, Matteo della Bordella, and Matteo De Zaiacomo, popped onto the north face coming from the east dihedral, the line attempted in 1981 by Phil Burke and Tom Proctor. After a quick chat with Korra, they agreed to follow behind.

Korra progressed quickly, with his usual decisiveness, passing their previous highpoint, onto immaculate granite, interspersed with mixed sections, past a very scary hanging mushroom - “mirame pero no me toques” pitch (look but don’t touch me), onto the Ragni route, which they joined at the base of the last rime mushroom. Korra dispatched this notoriously difficult pitch in barely 20’, and at 17:20 they were both standing on the summit. Davide and the Matteos summitted soon after.

After many attempts, and much effort, Tomy and Korra’s dream had finally come to pass. They had completed a new route on Cerro Torre, climbing the longest and most direct portion of the imposing north face. They thought of Jorge and Nico, with whom they had made many earlier attempts. At around 19:00 they started rappelling their route. Davide and the Matteos decided to sleep at the summit, and descend the Southeast Ridge the next day.

At the “honguito”, the shoulder part way down, Tomy and Korra waited until 10 p.m. for the temperature to drop, and the wall to stop dripping. They then continued to their bivy, which they reached at 2 a.m. They were tired, so they stopped to hydrate, and eat. They discussed continuing on, but changed their minds, deciding to get some rest. They covered their legs with their sleeping bag, and dosed off. A few minutes later, at around 3:30 a.m, they heard the sound of falling objects, which within seconds started hitting their surrounding. They both leaned to the right in an attempt to protect themselves. Soon after there was a massive crash. Mayhem. Tomy felt his body crushed, and his bones break, and they were both thrown downwards, their safety lines cut, but somehow miraculously stopped on small ledges two and three meters lower - this in the middle of an otherwise almost vertical face. They were in extreme pain. Tomy could barely move his upper body, while Korra could not move his lower limbs. For the following several hours they both assumed they would die. Korra did not move again. Based on his symptoms, it is presumed he had an internal hemorrhage, a broken pelvis, and back. The two meter by 1.5 meter rock flake that had been behind them at the ledge, protecting them, was gone. Although it might have protected them from a direct hit, possibly it was the flake rolling off that caused their injuries.

Their equipment had fallen or was scattered. Their inReach and painkillers were gone. Tomy started making the SOS signal with his headlamp, three short, three long. Several hours passed. He never saw a reply. Close to daybreak, under snow and ice debris Tomy found the mesh bag with the inReach. He typed several distress messages, but because of a weak satellite signal in the vertical face, they did not send. Tomy encouraged Korra to have hope. Korra in turn encouraged him to go down. Tomy, who eventually was diagnosed with a broken collar bone, five broken ribs, and a puncture lung, thought he was unable to. He could not move one hand, and could barely move the other. He was in a lot of pain. Korra insisted, and at the same time refused to be secured to the wall, and expressed his intent to jump-off. Korra understood that his die was cast.

When daybreak came, around 6:30 a.m, Tomy mustered all the energy he could, and started rappelling with the 50m section of rope that remained. He grabbed as much gear as he was able to find. He held onto Korra’s leg, crying one last goodbye. Korra encouraged him on, and they parted ways. On the second rappel the inReach messages finally got sent. Over the following 10 hours Tomy made very slow downward progress, taking over an hour for each 20m rappel. Unable to use his arms much, he used a jumar and his leg to pull down the rope. He passed-out at belays, and needed full concentration, pain avoidance, and motivation to continue. It was agonizing. He saw people on the glacier gazing at him, and knew that help was on the way, but he realized that if he wanted to survive, he had to get himself lower. At around 5 p.m. he reached the side of the Triangular Snowfield, 300m from the ground. Exhausted, in pain, and out of gear, he decided to stop.

In the valley below, fellow climbers had seen Tomy’s headlamp distress signals around 5AM, they replied (Tomy did not see it), and had given notice. A rescue attempt was underway. At the Niponino camp climbers organized and without a clear plan headed towards the face. Because Tomy was making steady downward progress, because of the danger caused by the day’s high temperature, and because they were unprepared to start climbing such a face, it was decided to wait. At 10:30AM rescuers left El Chalten on foot carrying a stretcher and other rescue gear. Two more groups would soon follow. At 1:45PM a helicopter arrived to Chalten, and was able to transport five climbers to Niponino, the highest landing spot considered safe. From there they made their way to the base, where they were joined by four more climbers, and soon after by Davide and the Matteos, who were just getting off the Southeast Ridge. At 6PM, with the temperature dropping, and having now a strong, capable team, four climbers started climbing up to Tomy, reaching him around 9:45PM and helping him rappel back to the ground. Because of his broken ribs it was impossible to piggy-back him, so he rappelled on his own.

In the mean time ropes had been fixed across the very broken, steep, treacherous glacier. At 1:30 a.m., when he reached the ground, Tomy was placed on a Sked stretcher/sled, and was lowered across the glacier to reach Noruegos by 4:30 a.m., where he was switched to a rigid stretcher, and lowered down the dangerous moraine towards Niponino. The weather worsened significantly, with wind gusts to 80km/h. In spite of this, the old military Bell helicopter took off from Chalten and flew in, landing at Niponino at 7:30 a.m. There it stayed, rotors turning, ready to leave, but it took the rescue team almost another hour and a half to get there. At 9 a.m. Tomy was flown off. In the nuking winds several people present expected the helicopter to crash on takeoff, but after wild sideways movement as it lifted, it flew off safely. It landed briefly in El Chalten, where Tomy was checked by a doctor, and them flew him to the hospital in El Calafate, 250km away.

When a week after the accident the weather provided a small opening, a drone was flown to establish the location of Korra’s remains, but they could not be found. It is presumed he fell and lies in the glacier below. Because the area where he is presumed to be is threatened by rock and ice fall, it was decided to abandon further efforts to find him.

At least 70 people participated in the all-volunteer rescue, which was an incredible display of the good-samaritan ethos that the local rescue team has cultivated over the last twenty years. Although some held hope that Korra could be saved, reality said otherwise. To be moved with the injuries he had, rescuers would have likely needed a vacuum mattress, a rigid stretcher, and means that simply could not be carried 600m up the east face of Cerro Torre, a notoriously dangerous place. Note that there are no pilots or helicopters in Argentina able to do long-line rescues. As crushing as it is to accept the loss of life, one cannot help but marvel at the miraculous effort that helped save a life. That it worked out as it did, was not due to the heroism of single individuals but the power of a collective, in which it doesn’t matter if you carry a heavy load, man a pack-raft across Laguna Torre, expertly pilot a helicopter, climb up to the injured person, help carry the stretcher, or send warm pizzas to tired, hungry volunteers at Niponino.

When at the very top Tomy asked Korra how they would call the route, he answered unequivocally, “‘La Norte’, what else would we call it?” And so the north face of Cerro Torre was climbed, but the price was far too high.

-

Ten days after the accident, I biked over to Tomy’s house mid morning. His son Satya and other kids were running around, playing, laughing. Tomy sat in a lawn chair, he looked haggard, his body still aching heavily. But life was sparkling. Simultaneously, half way around the world, in Korra’s parents house, a similar scene was unfolding - a large family lunch, joy infused by children and friends. The contrast with Korra’s silence, was deafening. Later that night, walking back from dinner with Seb, Jon, Lise, Jerome, Fanny, Camille, Christophe, Ali, and others, we remarked how in Korra’s shyness and social awkwardness, he might have been unaware how very much he was loved.

He was an independent, original thinker, full of unusual perspectives, with little tolerance for exaggeration, half-truths, or fabrications. He was an unquestionable talent, very determined, with endless passion for alpinism. He was particularly economic in his use of words, and had a very austere character. He always knew what was in condition in Chamonix, and was ready to share his knowledge with anyone that asked. He had climbed the north face of the Grandes Jorasses via 14 different routes, so his friends jokingly called it the “Grandes Korrasses”…

He was Corrado for most of his family, except his dad, for whom he was “Dado”, he was "Spiderman" for his nephews and nieces, he was ”Hard Korra" for some of his Chamonix friends, "Korrita" for his Argentine and Spanish buddies, and the “Count of Novara” for his friend Andrea. He was a man with no country - describing himself as being from Chamonix, without ever specifying a nationality. He had no allegiance, but to his own principles, and found himself more comfortable with the “others”, the immigrants, the oddballs, than with the establishment. He knew this website and my guidebook better than I did. I could always count on him for direct, honest feedback. I will miss and ache for him for many years to come. As his friend and mentor, Jeff Mercier wrote, “I love you Korra, I hate you for leaving.” May your stardust live on, with all its force, and creative beauty. So long.

|

Photos (click to enlarge)

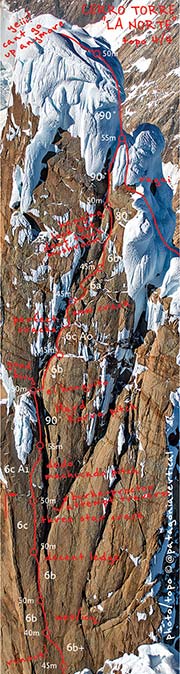

The line of La Norte. Click to enlarge.

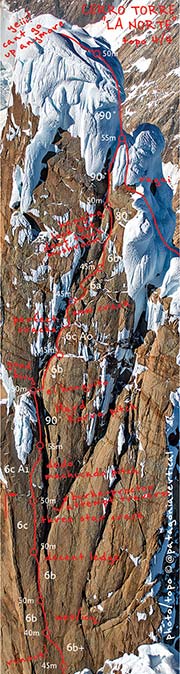

Lower 1/2 La Norte. Click to enlarge.

The lower north face. Click to enlarge.

Upper north face. Click to enlarge.

Korra climbing. Click to enlarge.

Korra at "el honguito". Click to enlarge.

On the summit. Click to enlarge.

Les Grandes Korrasses. Click enlarge.

|

Summary: “La Norte” was climbed between the 25th and 28th of January of 2022, by Tomás Aguiló and Corrado Pesce. It links “Un Songo Interrotto” (300m 6c), continues via the “American Torre Egger Route” (300m to 6c), to climb 550m of new terrain on the north face (7a A2 90˚), joining the “Ragni Route” at the base of the last pitch (50m 90˚). Altogether it climbs over 1200m. During the descent, Tomy and Korra were hit by falling debris. They both suffered severe injuries. Tomy was able to continue descending, and was rescued from the Triangular Snowfield, 300m from the ground. Korra is presumed to have fallen. His remains were never found.

The north face is crowned by enormous rime mushrooms. This makes the face particularly dangerous, as it is bombarded by falling debris almost constantly. It is unclear how temperature affects the behavior of these rime mushrooms, but it seems wise to only attempt this face when it is very dry, and when the freezing-line is very low, well below the summit. Beware. |